Kyle Novak is a Czech-born filmmaker and VFX artist currently based in Los Angeles. Earlier this year, he made waves as the winner of the Animation category for Ángulos de la Hora (Hour Angle), a rotoscope film following two strangers who agree to spend 24 hours together on one condition - they'll remain anonymous. This was the first year of the category being introduced to the Sony Future Filmmaker Awards, which made it an especially exciting win. In our latest interview, we chat with Kyle about his journey into animation, the creative process behind Ángulos de la Hora (Hour Angle) and what's next for the independent filmmaker.

Can you tell us a little bit about yourself and what inspired you to become a filmmaker?

I wish I had a more elegant answer to the second part of your question. I feel like I fell down a long flight of stairs and now I’m here. My background was in electrical engineering, and I originally focused entirely on the tech side of digital media. Back then, I had the arrogant belief that theater and the arts were pursuits for those who didn’t want to make practical contributions to society—a luxury for the nouveau riche. But working in engineering can be very isolating. You feel like a tiny cog in a vast machine and the result of your labor is never close enough to grasp. I can’t pinpoint when I crossed the aisle. It was a slow crawl.

Years ago, while still living in the Czech Republic, I made my first rotoscope animation, which sparked my fondness for that style—though I'm not strictly tied to it. Since then, I've been in the States, moving from city to city, working as an adjunct instructor at various art and design colleges. When my contributions to capitalism putter out, I spend weekends and summers being the impractical hippie I once disdained. So, in a way, I’m truly eating my old words.

What is Ángulos de la Hora (Hour Angle) about, in your own words? What would you like the viewer to take away from it?

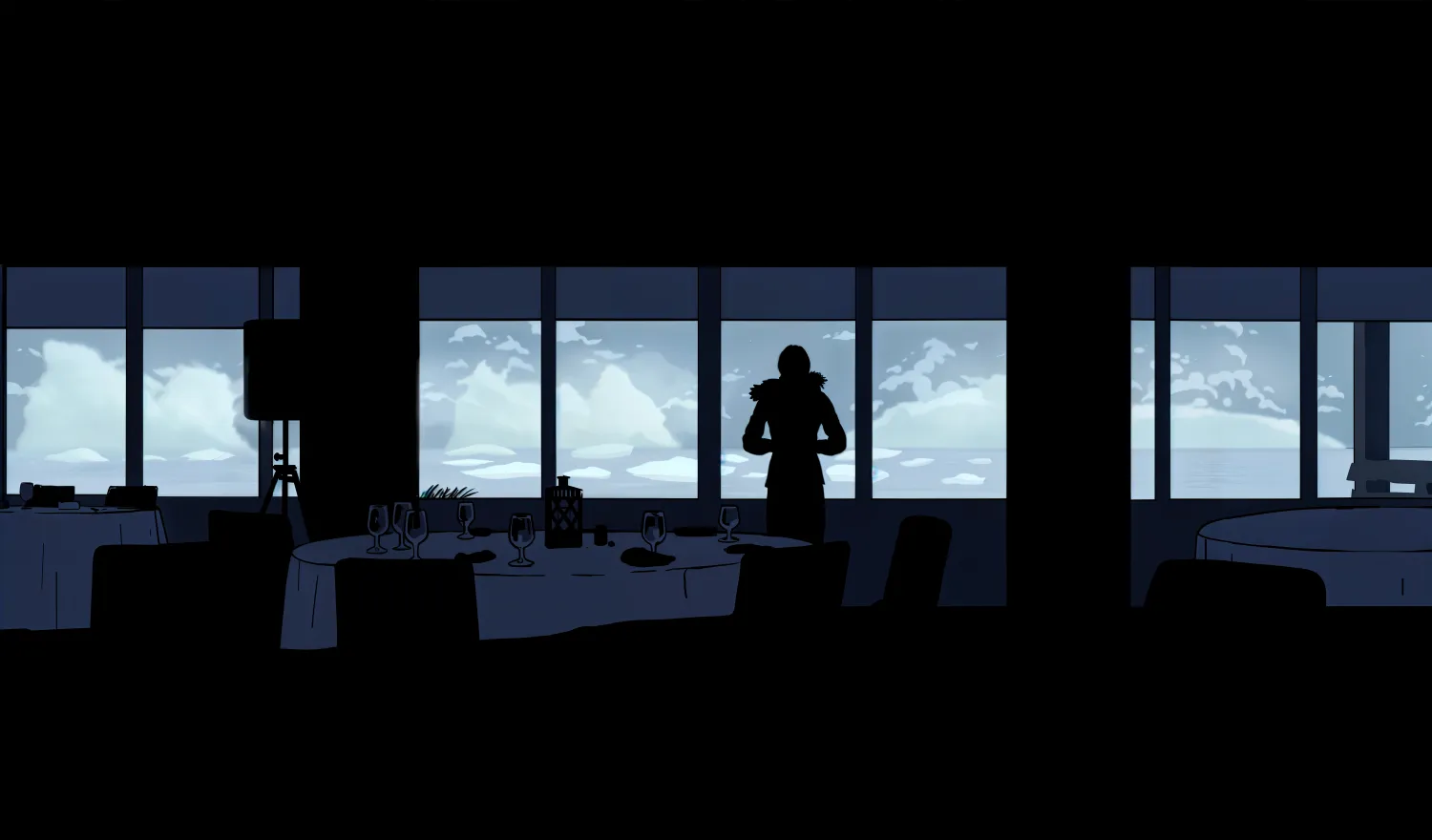

Hour Angle is an interpolated rotoscope animation about two strangers who decide to spend 24 hours together, but only on the condition of anonymity.

I think my main intention was to tap into our tendency to be selective about what we focus on when watching a film. I often find myself doing this as an audience member. Sometimes I’m intensely focused on the dialogue, while other times I let the dialogue fade into the background and just wallow in the atmosphere of the scene. I thought I could lean into this and reward viewers by divulging different layers of the story subject to how it’s watched.

The decision to animate was also part of that, especially in using rotoscope, which has its own stylistic quirks, especially in how it renders characters as uncanny versions of themselves. I find when thinking back on people I briefly met, I can scarcely recall them as complete people, distinct from their space or time. The experience itself is very “other” and I wanted a way to present that formally.

Anyway, that’s all nerd drivel. These motivations aside, I would really like viewers to find something relatable about this quality we all have to be so lovelorn— whatever the circumstances.

Can you share some insights into the behind-the-scenes process of making your independent short animation? How did you approach collaborating with your peers throughout the project?

For interpolated rotoscope, you need live footage, so the entire process was just like that of any short film. I had my collaborator Brendon, who acted as DP. For a while in pre-production, it was just us. At some point, we needed someone with serious organization skills and I reached out to my Russian friend, Kseniya. Still, it was pretty much this three-person crew for production. In retrospect, we were all doing a dumb circus routine where each person one-man-banded various roles. I wish I could romanticize it but having no budget just sucks. I think I had managed to successfully get only one filming permit, and it was for the airport to avoid TSA interrogation rooms.

During post-production, I was alone for a good while. After about a year, I luckily managed to finagle some really talented people to come on board. Completely unintentionally, I had a little multi-hemisphere crew consisting of someone from Prague, from Montevideo, from Moscow, and from Brussels. But with plans for over 14,000 frames of animation and 10 uninterrupted minutes of music, almost everyone was crawling on their hands and knees by the end.

What is your favorite scene in the movie and why?

I can’t help but have personal issues with every scene of my project when I turn in the final print. At some point in the process, there has to be a hard-stop, and when that comes around, you’re forced to look in the mirror and say: “Okay, that’s it. Now all that’s left is to mull over the missed opportunities and sulk at the things you could have done differently.”

To answer the question, the scene I’m least annoyed with is maybe the ice-bucket sequence at the end, if only on a basic emotional level. I think it’s very human to ascribe these little talismans to our past relationships, especially romantic ones. In this case, the transience of object itself, the ice cube, and the protagonist’s means to preserve it — I guess I still like all that. But I’m at that stage of “done” where I can’t watch the thing anymore.

What are some of the unique challenges of creating animated films and how did you overcome them?

Animation can definitely be a double-edged sword. On one hand, it’s an incredible way to experiment, especially for those of us on low or no-budgets. That being said, interpolated rotoscope is a rare beast. You’re certainly reliant on what you shoot, but then the frame becomes a canvas, and there’s an opportunity to demolish and re-build.

On the other hand, animation also has this unfortunate tendency, at least in my view, to easily become a pastiche. On top of that, given that most animation is targeting young people, the stories can sometimes allow for petty moralisms or cheap heart-string-pulls. So you have to be careful to avoid that.

I’d say the key unique challenge in animation is to avoid these pitfalls. How does one overcome them? It’s meticulous planning.

Who is your biggest inspiration?

I guess there’s two kinds of inspiration. I’m clearly inspired to do things for my family and loved ones. Their very existence in my life is an inspiration. Then I’m inspired by artists and filmmakers who do superhuman feats. I wouldn’t say there’s a singular person I would make mention of, but I would like to point out a movement. I’ve been in awe of the Romanian New Wave. It broke ground I didn’t know could be broken. It really made me realize there’s so many new ways to approach filmmaking, so many modes and methods untapped.

What's the best piece of career advice you've ever received?

The best career advice I’ve received is to look for the network I’m already part of, whether through birth or sheer luck, even if I’m not fully aware of it. This existing web of connections is often the strongest, made up of people who are most likely to take risks on your behalf. They also may be unrelated to filmmaking, but that’s irrelevant—power and resources cross industries. Unfortunately, I can’t remember who shared this insight with me.

On the flip side, there’s a lot of bad career advice out there. The suggestion to constantly network with peers at parties and mixers often treats people like transactional automatons rather than human beings, which feels incredibly cynical. I also frequently come across advice that might have been relevant a decade or two ago but is outdated today. Things change fast and people can sometimes be slow to notice that.

What are you currently working on?

For the past year, I've been doing weekend shoots with a friend from LA on a longer-form mixed media project. Right now, I'm in the honeymoon phase with it, but we'll see how things evolve once we get into post-production.

When it comes to a more traditional, higher-budget feature film, I firmly believe that a strong screenplay is everything, so it’s all writing for now. That may sound obvious, but it's not a sentiment shared by everyone. There’s a lot of "just go shoot anything" thinking out there. I've long wanted to film something really meaningful in the Czech language, so once that script is ready, that's my main future goal.

The Sony Future Filmmaker Awards 2025 are open until 12 December 2024. Enter your short film into one of the four categories: Fiction, Non-Fiction, Animation, Student to win a trip to Los Angeles where you'll attend an industry-immersive workshop program led by Sony Pictures executives. Submit now.

Kyle Novak

Kyle Novak is a VFX compositor and Houdini artist, having lived and worked in New York City, Miami, and Los Angeles. Originally in tech, Kyle's focus was on integrating emergent digital technologies into post-production workflows.

His short animation Ángulos de la Hora (Hour Angle) won the Animation category in the Sony Future Filmmaker Awards 2024, which was announced at the awards ceremony back in May.